The Digital Markets Act will enter into force today: an overview

SÉRVULO PUBLICATIONS 01 Nov 2022

Context

Approximately two weeks ago, on October 12, the official version of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) was published in the Official Journal. This regulation enters into force today, November 1, but will only be fully applicable on May 2, 2023.

In the context of globalization, massification of smartphones, high-speed internet, algorithms and AI, digital technologies have been responsible for a fast-paced revolution in our society and so the functioning of markets.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also contributed to an increasing dependence of online services that allowed digital platforms to grow more powerful. Numerous types of activities (e.g., shopping, learning, working) switched from offline to online. Therefore, a small number of digital platforms maintained or strengthened positions of dominance in the European Union (EU) market, often performing abusive conduct (Art. 102 TFEU).

Problems have risen since the law is often slow adapting to address potential negative effects of digital services. Whilst platforms offer new and cheap priced services to users, they simultaneously create barriers for new players to enter the market.

Law has been called to respond to multiple issues such as uncompetitive behaviour, but also to solve other law-related issues including the reduction of job security, the avoidance of taxes, data privacy and compliance standards.

To mark the importance of tackling this regulatory challenge at the EU level, the European Commission (EC) has appointed, for the first time, a Commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, specifically tasked with the political priority of a “Europe Fit for the Digital Age”. Together with the Digital Services Act Proposal (PDSA), the Data Act, the Data Governance Act and the AI Act Proposal, the DMA intends to change the reality of digital markets and platforms.

The Digital Services Act Proposal (PDSA): key aspects and differences

Before diving into the DMA, it is important to compare it to the other recent piece of legislation, the Digital Services Act Proposal.

The PDSA applies to all “intermediary services,” while the scope of the Digital Markets Act is limited to “core platform services” offered by “gatekeepers”. The Act regulates the obligations of digital services that act as intermediaries in their role of connecting consumers with goods, services, and content.

The PDSA establishes a robust transparency and accountability framework for digital platforms, helps protecting users and fundamental rights online, and provides a uniform framework in the EU.

The proposal is aware of the potential harm caused by very large online platforms (VLOPs). In order to prevent risks, the PDSA includes additional obligations for these platforms.

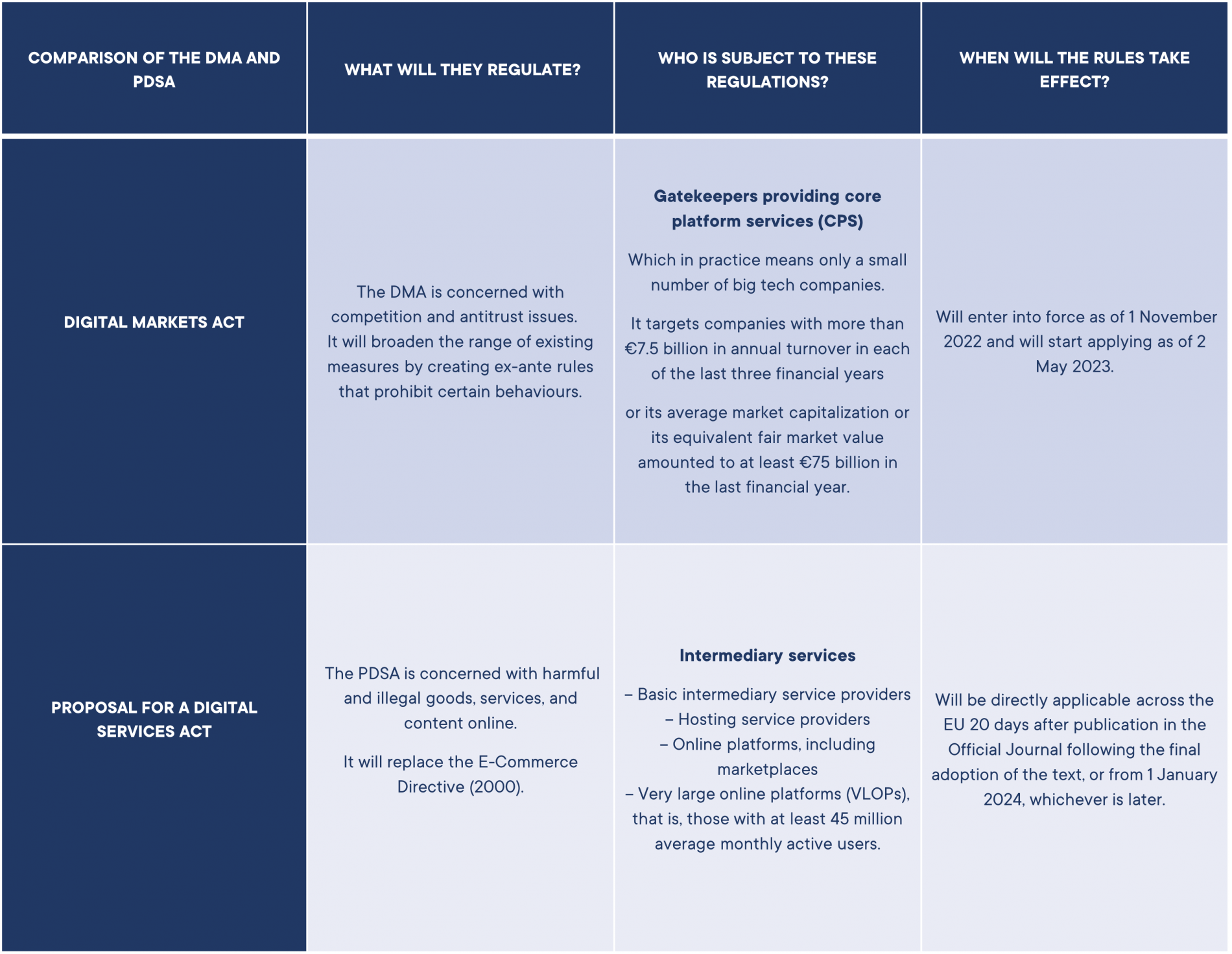

For the purposes of this update, only the differences between the DSA and DMA will be explained. To summarize, this chart might be of use:

The Digital Markets Act

The goal of the DMA is to establish “fair and open digital markets” by targeting digital platforms that act as gatekeepers and provide a harmonised framework with legal certainty for businesses, tackling regulatory fragmentation in the EU.

The DMA complements competition law at EU and national level. It amounts to sectoral regulation in the form of secondary EU law. The Act addresses unfair practices by “gatekeepers” that either fall outside the existing EU competition rules or cannot always be effectively tackled by these rules because of the systemic nature of their behaviours. The DMA will thus minimise the harmful structural effects of these unfair practices ex-ante, without limiting the EU's ability to intervene ex-post via the enforcement of existing EU competition rules.

The DMA does not apply to all digital platforms, but only to those qualified as “core platform services” (CPS). CPS include services such as search engines, web browsers, virtual assistants, video sharing platforms, etc.

The scope of the DMA is further limited to platforms designated as “gatekeepers”. The gatekeeper must a) have a size that impacts the EU internal market; b) provide a core platform service which is an important gateway for business users to reach end users; and c) enjoy an entrenched and durable position in the market.

Platforms that satisfy the above criteria are presumed gatekeepers but can rebut the presumption and submit arguments to demonstrate that, due to exceptional circumstances, it should not be designated as a gatekeeper despite meeting all the thresholds.

Additionally, the EC may launch an investigation to assess the specific situation of a given platform and decide to identify the platform as a gatekeeper, even if it does not meet the quantitative thresholds. This can be the case of the EC designating a gatekeeper based on being foreseeable that it will enjoy an entrenched and durable position in the near future.

The EC will be the sole enforcer of the Act. This centralized enforcement aligns with the gatekeepers' transnational activity and the DMA's objective to provide a unified framework with legal certainty for platforms in the EU. At the same time, the EC will cooperate with National Competent Authorities (NCAs) for the application of the Act.

The DMA gives the EC the power to, among other things, request platforms and NCAs for information; conduct interviews and take statements; conduct necessary platform inspections; order interim measures against a gatekeeper; and take steps to monitor the DMA's effective implementation and compliance (e.g., by appointing external auditors).

Prohibitions and Obligations imposed on gatekeepers

The DMA establishes a system of prohibitions and multiple positive obligations for gatekeepers (“dos and don’ts). Some examples are:

- Prohibition on restricting switching

- Prohibition in self-preferencing in ranking

- Prohibition on making termination conditions disproportionate or difficult to exercise

- Obligation to allow app un-installing and changes to default settings

- Obligation to allow interoperability

- Obligation to ensure data portability

- Obligation to inform about concentrations

- Obligation of an audit

Failure to comply with transparency and cooperation requirements may result in fines of up to 1% of the platform's annual global turnover. The EC may also impose periodic penalty payments on platforms, including gatekeepers when appropriate, and associations of platforms, up to 5% of the daily average global turnover in the previous financial year.

Gatekeepers may face heavier sanctions for violating the DMA, including fines of up to 10% of their global annual turnover. The fine might rise to 20% of the global annual turnover for repeated offenses. If a gatekeeper violates the rules three or more times, the EC can impose a temporary ban on mergers or impose divestiture requirements.

Concluding remarks

An aspect that has been criticized in the DMA is its very inflexible system of prohibition. Art.5,6 and 7 contain a numerus clausus of per se rules. The per se rules do not require proving the actual harmful effects of a conduct but outlaw that conduct as such.

On the one hand, this enhances legal certainty. On the other hand, the per se rules may prohibit a conduct that does not cause harmful effects (“false positive”) and may fail to consider a harmful conduct as such (“false negatives”). In addition, these rules can be seen as imposing a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach on gatekeepers with severely different business models. At the same time, the intrusiveness of these obligations must be weighed against the demonstrated ability of gatekeepers to dodge regulations.

The DMA imposes general remedies, while competition law imposes case-specific remedies. Therefore, the general remedies of the DMA might be, to some extent, limited compared to some competition remedies. Exploiting the opportunities created by the coexistence of both is the way to go for the EC.

The DMA will only be effective if there is adequate enforcement and compliance. The EC will be the sole enforcer of the DMA. Nevertheless, there have been concerns that the EC will only be able to fulfil the task if it has sufficient human and technical resources, including digital experts.

The success of the DMA will, to a great extent, depend on its effective application, meaning that the enforcement, timely decision-making, human and technical resources, as well as compliance will be key factors.

Despite all the criticism, the DMA intends to tackle the current digital challenges by imposing stricter rules, creating new bodies (such as the e Digital Markets Advisory Committee and the High-level group), imposing significant fines (up to 20% of the global annual turnover for repeated offenses), imposing interoperability requirements, prohibitions on self-preferencing and on restricting switching, creating obligations to allow app un-installing and changes to default settings and an auditing obligation, among others.

The DMA marks an important turning point and a much-needed piece of legislation. It creates numerous obligations on gatekeepers, signalling a new era of digital regulation in the EU that will foster a new kind of interplay between competition law enforcement and ex-ante regulation in the digital field. Such interplay will require continued examination and critical analysis.

Miguel Máximo dos Santos | mxs@servulo.com